Fredericke Winkler

Textiles | Interior | Design | Education | Sustainability

AMD SCI x Modemuseum Meyenburg

Community Collaboration: “Made in Brandenburg” Exhibition

This project explored how rural regions can be more meaningfully included in cultural exchange and democratic participation. In collaboration with the Modemuseum Meyenburg, located in Brandenburg’s Prignitz region, we worked to create a space where local textile traditions could be shared and acknowledged within a museum context.

Seven students from five different countries took part in the initiative. Local residents were invited to contribute handmade textile objects—such as knitted, woven, embroidered, or sewn pieces—and to share the personal and historical stories behind them. The aim was to create an inclusive exhibition that highlights the value of everyday craft as part of the region’s material culture.

The project unfolded over three key phases: an introduction to the museum and its history, a collection day for community submissions, and the final exhibition opening. The number and quality of submissions exceeded expectations, presenting students with the challenge of cataloguing and curating the material as professionally and systematically as possible. This process included questions around classification, selection criteria, and how to appropriately present personal stories alongside the objects.

The result was the exhibition “Made in Brandenburg,” which showcased not only the submitted textile pieces and photographs, but also documented the project process itself. Interview recordings and other materials offered insight into the contributors’ perspectives and the significance of their craft within the broader context of cultural heritage.

As student Andrés Valdivieso reflected:

“It was a soft and gentle slap of reality in the face to get to know them and learn about the historical background of the people from Brandenburg. It felt super honest, raw, and warm. So it’s an instance that normally we would not have access to—and I think not even other Germans either. The main part of this experience was to give them a platform to showcase their talents and to share their history.”

Through this project, I gained a deeper appreciation for the role of museums in fostering cultural participation and recognizing craft as a form of intangible heritage. It strengthened my motivation to continue collaborating with museums and to further explore this area of the fashion field—especially as it relates to the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability.

Involved Students: Jonas Austenfeld, Cheryl Lam, Anna Lammer, Pearl Neithercut, Solène Schlömann, and Andrés Valdivieso and Bernadita Solis, who used this project as case study for her Master Thesis.

Posterdesign by Bernadita Solis

Special Thanks fo to our project partner Modemuseum Schloss Meyenburg and director Barbara Schrödl for her kind and brave support:

Keynote: “Collective Authorship and De-Growth”

At the Ecology and Art Conference 2024, hosted by METU University in Budapest, I had the opportunity to give a keynote exploring the intersection of collective authorship and de-growth within creative practice.

Creative processes are rarely, if ever, individual acts. Artists, designers, and writers are shaped by cultural contexts, collaborative environments, and the broader productive structures that enable their work. Yet, modern concepts of authorship remain closely tied to individual attribution - essential for both recognition and systems of value in science, the arts, and the economy. This creates a fundamental tension that continues to be critically examined across disciplines.

In my talk, I addressed how artist and craft collectives have challenged and redefined authorship, sometimes by intentionally stepping outside individual attribution systems. Drawing on examples from activist and creative communities, I discussed four key dimensions of collective authorship: Anonymity as a form of resistance, A pluralistic worldview and shared decision-making, The relationship between creative practice and productivity, Property, access, and participation in authorship

Through these lenses, I considered how collective authorship can serve as a counter-model to capitalist structures, particularly by resisting conventional measures of productivity and ownership. I argued that collective authorship has the potential to align with de-growth principles, offering alternative pathways for sustainable and socially engaged creative work.

I’m grateful to METU University for the invitation and the chance to be part of such a timely and relevant conversation.

More about the conference: https://www.metubudapest.hu/ecology-and-art-conference-2024

Semester Project on Cross-Cultural Collaboration

As part of our semester project, we explored the concept of cultural sustainability through hands-on experience. In collaboration with WhyWeCraft®, six students took part in a five-day immersive trip to Romania, where we learned about the country’s rich history, traditional crafts, and the cultural initiatives behind the organization.

The heart of the project was a co-creation process: each student worked closely with craft custodians from WhyWeCraft® to explore a textile product that embodied the principles of cultural sustainability. Each day brought new encounters—with local artisans, hands-on workshops, and discussions grounded in the theoretical foundations we had studied.

This diverse program, curated and led by Monica Boța-Moisin, offered a deep dive into traditional knowledge-sharing practices. For many of us, it reshaped our understanding of what it means to collaborate across cultures, and what respectful, inclusive co-creation can look like.

A heartfelt thank you to Monica Boța-Moisin, our guest lecturer and guide throughout the project, and to the amazing custodians Elena Neagu, Katalin Kovacs, and Virginia Linul for generously sharing their time, knowledge, and traditions with us.

Involved Students: Aerielle Rojas, Hilde Eriksen, Hanie Zadsar, Selda Palaci Alaçam, Jyotika Bhardwaj, Bernadita Solis

Project period: Summer Semester 2024

WhyWeCraft® operates under the Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative® (CIPRI) and supports craft custodians through the 3C Rule: Consent. Credit. Compensation™. This legal and ethical framework has been applied in communities across India, Laos, Guatemala, Romania, and Mexico, and aspires to global recognition. https://whywecraft.eu

Circularity of Regional Fashion

As a representative of AMD Berlin, I had the privilege of participating in an Erasmus BIP program, a collaborative effort between METU, SAPIENTIA, and AMD Akademie Mode und Design. I joined the project with a colleague and ten students, many of whom were visiting Budapest for the first time. Over five dynamic days, we explored the complexities of circular fashion and its relationship to sustainability in the European context. The program was filled with engaging workshops, discussions on EU strategies, and case studies on sustainable fashion models. We worked together to understand the challenges and opportunities of circular design, from overproduction in fast fashion to the importance of transparency in the fashion industry. Through group projects, film screenings, and hands-on workshops, we gained a deeper understanding of how small brands can thrive in a sustainable fashion market while contributing to the larger EU goals of circularity. The experience was both enlightening and empowering, offering fresh perspectives on the future of fashion.

Design Direction Hodsoll McKenzie 2022

REWILD - Rewilding is about letting nature take care of itself, enabling natural processes to shape land and sea, repairing damaged ecosystems and restoring degraded landscapes. Through rewilding, wildlife’s natural rhythms create wilder, more biodiverse habitats with an emphasis on humans stepping back and leaving areas to nature.

Rewilding, when applied to humans, could also mean our return to the essentials, in order to reconnect with nature and our natural state of being. A return to the untamed aspect of ourselves, inherent in all of us. While the world becomes increasingly complex, a nature-oriented lifestyle promises conditions that are coherent and fair for every creature. It also promises space for spontaneity and joie de vivre.

In this context, the conservation of natural habitats is no longer sufficient: the desire to create new habitats, a new coexistence with nature and its wilderness – and consequently one’s own wildness – is the goal of this “Rewilding“ concept.

With this in mind, this collection is dedicated to all the endangered species that will vanish forever, if humankind doesn’t learn to coexist with nature now. It is a celebration of nature’s diversity, which we often enjoy as lifestyle but must also learn to cherish as something vulnerable and in need of protection. But it’s also about stepping back and allowing ourselves to lose control and letting the wilderness teach us how to live a meaningful life.

Creative Designer: Fredericke Winkler | Photography: Georg Roske | Set Styling: Berit Hoerschelmann (Liganord Agency) |

Video Clips: Elena Schröder | On Site Project Coordination: Oliver Schmid | Art Direction Digital: Orkide Daniel | Location: Buenavista Lanzarote Country Suites | Location: @famarasoulsuite | Location scout: @orkidee_studio

Design Direction Hodsoll McKenzie 2021

UTOPIA - Is there any greater incentive than the dream of a better life? And is there any greater motivation than a better life for all? Surely not. The dream becomes a vision and the vision becomes a concrete plan for the best possible future, a utopia. And even if it cannot be realised in its entirety, it can still serve as a guiding light and goal.

Because one thing is for sure: the path to a better future is much easier to follow if you come equipped with a good plan. And this is the path that Hodsoll McKenzie have chosen to take with their 2021 collection.

Moving forward, the goal is to create solutions for environmental issues within the industry. Natural materials will be sourced responsibly and within the local region when possible. The production processes will strive to be environmentally friendly and innovative; also the designs shall honor their textile culture and history. The fabrics are intended to enable users to design spaces that are in harmony with nature, not just aesthetically but intrinsically.

These fabrics aim to help create an oasis that simultaneously promotes safety, health and invites people to dream of a better future. After all, it is no coincidence that many a utopian novel is set on a desert island, as this landscape enables one to implement possible solutions on a small scale.

Many of the fabrics in the 2021 collection bear the names of real and fictional islands. The Garden of Eden is as present as an animal that has paradise in its name. This collection represents Hodsoll McKenzie's first steps towards sustainability. The journey is long, but what better reason to embark on an adventure towards the prospect of a better future?

Photographer - Georg Roske / Set Styling – Berit Hoerschelmann | Helping Hands – Jessie May Thomson & Giulia Consiglio | Digital Operator – Luis Bompastor

Design Direction - Hodsoll McKenzie 2020

As Design Director for Hodsoll McKenzie I was responsible for the design and the development of the collection, the art direction of the imagery as well as the overall concept of the promotional material.

In this is what the collection is about (German version below):

The first World’s Fair in 1851 was a spectacle, the likes of which had never been seen before. More than 17,000 exhibitors from 28 countries accepted Prince Albert’s invitation to come to London’s Hyde Park and set up exhibits to show off the progress and wealth of their country. A flood of goods from all over the world poured out across more than ten hectares of land, transforming the event into the 19th century’s very own Babylonia. The Great Exhibition, as it is often called, still serves as a snapshot of industrial history and was also the birth of British design. However, it is also considered the birth of the Arts & Crafts movement, which feared a decline in quality and culture due to the upswing in industrial production. This year's collection by Hodsoll McKenzie operates in this area of tension between futurity and awareness of tradition.

Die erste Weltausstellung im Jahre 1851 war ein Spektakel, das es seinerzeit noch nie gegeben hat. Mehr als 17.000 Aussteller aus 28 Ländern folgten der Einladung in den Londoner Hyde Park und zeigten Exponate, die den Fortschritt und den Reichtum ihrer Herkunft bewarben. Auf mehr als 10 Hektar ergoss sich ein weltumspannendes Warenmeer, welches die Veranstaltung zum babylonischen Sinnbild des 19. Jahrhunderts machte. Bis heute gilt die Great Exhibition als historischer Augenblick in der Industriegeschichte sowie als Geburtsstunde des British Design. Sie gilt jedoch auch als die Geburtsstunde der Arts & Crafts Bewegung, die durch ebenjenen Aufschwung der industriellen Fertigung einen Niedergang der Qualität und Kultur befürchtete. In diesem Spannungsfeld zwischen Zukunftsoptimismus und Traditionsbewusstsein, bewegt sich die diesjährige Kollektion von Hodsoll McKenzie.

https://www.zr-magazine.com/hodsollmckenzie

Design Direction Hodsoll McKenzie 2019

In Mai 2018 I undertook the Design Direction for British interior textile brand Hodsoll McKenzie under the roof of textile editor Zimmer & Rohde. This is my first collection.

My very first step was to define what the brand stands for. Hodsoll McKenzie has always built a bridge between ratio and temper, sophistication and a down-to-earth-attitude, Great Britain and USA as well as between British history and international zeitgeist. With this collection we refocus on these roots, these strong and just seemingly contradictory characteristics of Hodsoll McKenzie.

Hence my first collection ‘Brigde’, goes back to the Great Britain of the 1930s when artists and designer have been driven by the pervasive impact of the industrialisation which has radically changed means, esthetics and possibilities but also has threatened slow handicraft processes. A new simplicity has arosen, function was no longer just a bothering obligation but a source of beauty. These times were full of contradiction: serial production versus manufacturing, rediscovering nature while urbanizing, appreciating tradition and seeking for innovation. All is about decoration against pureness and hard materials combined with soft ones. Using gentle colors and forms to create cosyness in the straight interiors of that time. A style that is more up-to-date than ever and build the common base of contemporary taste and meaningful design of the new century.

It is the times when artists like British sculpturist Barbara Hepworth and graphic designer Marion Dorn created one-of-a-kind textiledesigns for Edinburgh Weavers and Warner.

Meanwhile US-artists like Milton Avery, who is said to be the American Matisse, as well as artist Mark Rothko have evolved a radically new understanding of colors.

Brigde transfers this field of tension betweentradition and innovation on todays interior lifestyle.

The colors of the collection remain true to theclassic Hodsoll McKenzie palette – soft andlight watery tones, blue hues and elegantearthy, neutral tones. But they are going to be accentuated by bold and warm colors such as mustard, terracotta and a bright agave green –all inspired by the landscape paintings of Milton Avery and the urban field painting of Mark Rothko.

This is why this collection bridges the gap between yesterday and tomorrow in every respect as well as between cosy British country houses and sophisticated living spaces of todays metropolises. Adorable but quiet, not on stage but creating the set of it, the collection provides confidence of style and refinement.

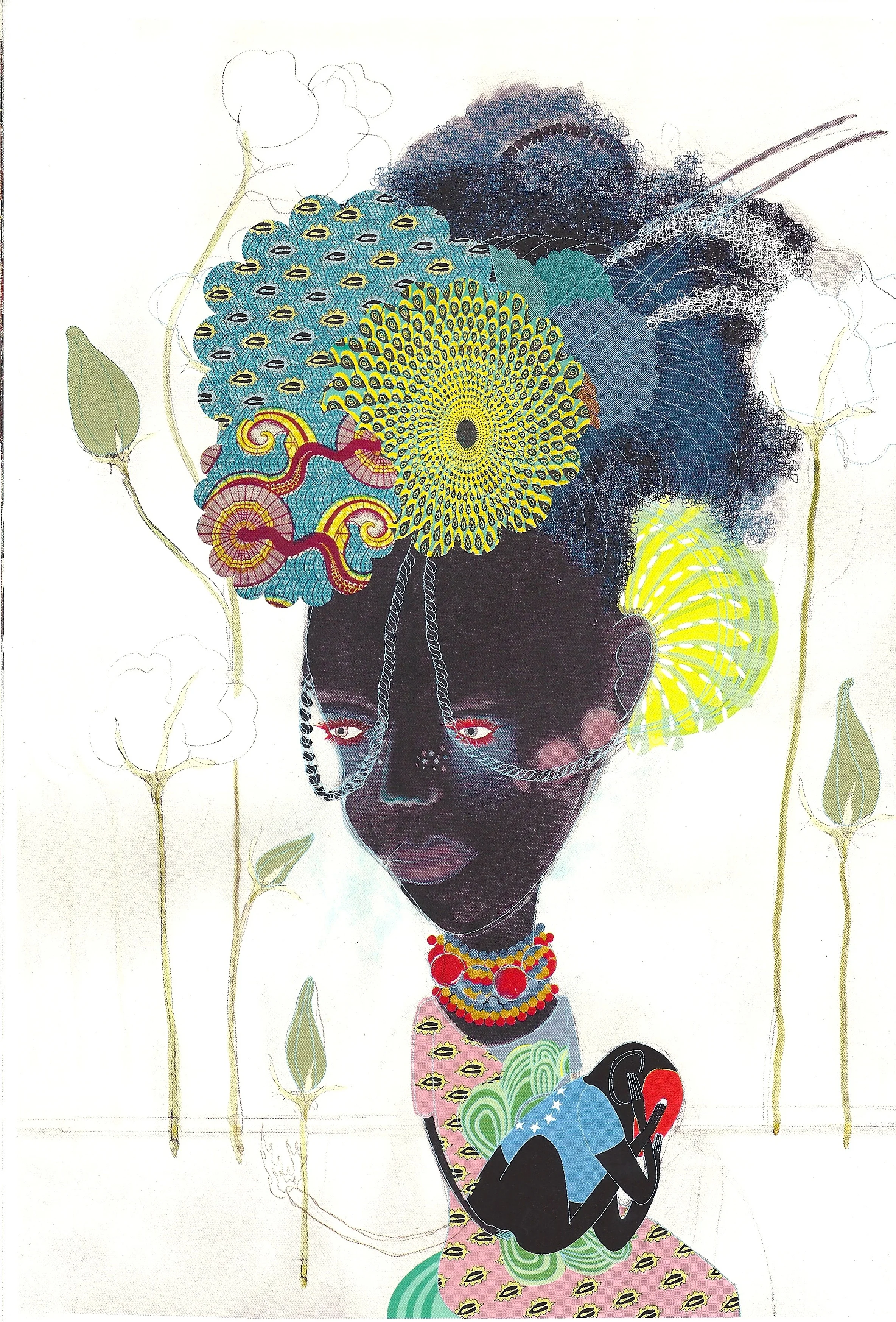

Art Collaboration for ZR ATELIER - Creative Concept

My task was to create an artistic representation for the Zimmer + Rohde Fall 2021 collection. I researched four collage artists from different countries and provided them with the collection images, so they could work them quite freely into collages in their personal style. The result are these wonderful works, which are actually all handmade.

Many thanks to the artists:

The Scissorhands - Munich

Paola Dcroz - Spain

Rachel Anne Duffy - New York

John Whitlock - New York

Design Talk

The magazine Deco Home (03/2020) published a wonderful interview I did with my two colleagues Allison Block (Design Director Travers) and Elodie Deletoille (Design Director Etamine) during the Deco Off in Paris in January 2020. Since many colleagues and friends asked me for an original version in English, I want to make it available here in full length to all of you.

Fredericke: Such a rare and precious circumstance that the three of us are physically able to sit together and not communicating via text. Since you both have just launched your first collections for Zimmer & Rohde and I am about to finalize my second, it feels like a good moment to reflect on our brands and what makes them unique and different from each other.

Elodie: Well, at the center of the DNA of Etamine is color, specifically French colors. And French paintings are a good first way to look at them. It is then that you can catch an international point of view about what is considered French color, and that is where the idea for my first collection came. When I was in the Matisse Museum a year ago I thought it was interesting to keep this in mind. The second step was to create a precise color concept. I wanted to focus on flowers, and decided to explore seasonal colors: winter colors which are more snow white, pearl and grey. Then spring colors: the purples, the fresh greens. And if you go further into summer, the colors are more generous with warm pink, apricot, orange and lemon yellow. I finished the palette with more rustic Autumnal colors like a terracotta, warm beige and burgundy.

Allison: Interestingly, my starting point was very different. I felt like the brand itself had lost its identity a bit over the past few years and for my first Travers collection it was important to me to find a way back the brands roots. I started by scouring the design archive, and it is there I found 3 designs to revive in my first launch, one of which was the original document for the elephant print ‘Singita Parade’. This print was sort of the birth place for the ‘Out of Africa’ collection. I saw this pattern and I thought ‘I have to use this!’ It was then that I started layering in other designs and patterns that worked well together to create a larger story. Original artwork was developed to create an embroidered Safari scene to round out the collection. Similarly, for the ‘Central Park’ collection it started with the two main designs. During the same week I first found a floral document in the archive of an Italian printing mill and then I saw the ‘Central Park Toile’ in the design portfolio of my intern. There were two very different stories and I wanted to explore both, so instead of one large collection I created two smaller ones.

Elodie: I had to start from scratch, because there is no Etamine archive, which makes it difficult. Of course I worked with mill archives. I found ‘Le Bouquet’ in the archive of a printing mill in Manchester and ‘Polynésie’ at a mill near Lake Como in Italy.

Allison: For color I don’t work with a set color palette. I like to think of color independently for each design, with the intention to be cohesive as the designs work together. In America it’s a little bit different where we don’t want the same green or the same blue across every pattern in the collection. I love to have the nuance and the cast twists to create this larger lifestyle story.

Fredericke: Before developing a collection for Hodsoll McKenzie I invest a lot of time in the research. And then during the process of development, it’s important for me to remind myself about my initial excitement during the research stage. What was the original document that I was amazed about in the first place? Often I push documents and designs further with coloration and by modernizing the patterns. I sometimes lose the big picture of the original during this process. And then I go back and notice that it was more about the blue that excited me, and I suddenly know that I must conserve this blue. I always try to keep the original color of my documents in the loop until the last decision phase.

Allison: Yes, It’s interesting to see how you can come full circle sometimes. I too always try to include the original documentary colorway in the mix. I’ve been coloring multicolored prints for 15 years and the quirky unexpected color combinations found in the original historical documents are something I like to preserve. For instance, we included the original coloration for ‘Cape Floral’ in the collection. The design came from the mill in the UK and the colors on the historical document really suited the print. We included it even though it doesn’t necessarily layer into the larger color palettes. I like to think that everything has to stand on its own independent of the larger collection.

Fredericke: Developing a Hodsoll McKenzie collection, I focus on three processes at the same time. The first is entirely emotional, I see fabrics or designs and I fall in love. Here I often notice that I always go for a certain texture or color, maybe even one I did not like before and all of a sudden it speaks to me. Then there is the technical process, for instance, introducing a certain new category or style in the collection. The third process is intellectual. Since I am a design theorist, which means that I studied the psychology, philosophy and history of design, I decide on a particular moment of British design history as inspiration. And from there I explore the collection. So for 2020 I went back to the 19th century and the beginning of industrialism to capture the tension of traditional handcraft versus new industrial techniques of manufacturing textiles. This theme is important for the DNA of Hodsoll McKenzie.

Allison: Our two approaches are so different. It’s very rare for me to be able to have such a clear point of view of what I am trying to accomplish before I start working. It is a much more organic process as I collect and see how I want it to take shape. It’s just kind of incredible when I start layering the qualities, designs and patterns together, how they start to take on their own personality and character. There will always be a starting point and then the theme solidifies as I start working.

Elodie: I went to this exhibition of Henri Matisse and I found it to be a good guideline, but I do not stick 100% to these guidelines. I store it somewhere in my head, but do not focus on that to create my collection. I like to fall in love with the designs I find in the archives of mills and suppliers. Designs can talk to me, I think about how maybe they may have a chance in the collection and how I can tell a story. The structure of the collection is more about how a room is designed. As soon as I select a design I determine its use. Is it for the living room because it’s more expensive and people want to show it off? Or is it maybe more discreet and would it create a very relaxed and cozy bedroom interior? A sheer might be the perfect choice for the kitchen because it’s washable. I always try to picture how it will be used. This is very important for me.

Allison: I feel that for Travers I wanted to build a lifestyle brand, meaning that the collections offer a complete range of fabrics to use throughout the home. This year we’ve added a new category for Travers. We did not have wide width sheers, and it felt like a missed opportunity. And so when I’m creating a collection I am thinking about the need for upholsteries, draperies, decoration and sheers. It is important to also consider every room and house, otherwise you again loose opportunities. That is why I believe color is so important. You can sort of decide what environment and room in the house you want to put the textile based on mood and color creates this mood.

Elodie: Personally my favorite room is living room, with the main focus on my fireplace. I love the moments when you are around the fireplace, even in summer. It is the place where you join people and I like to make this area really comfortable, to gather important people around me. I have beautiful paintings on my wall. When developing the Etamine collection I also like to combine art, furniture, architecture and see how they talk to the textiles.

Allison: Same here, I am always thinking about the living room first, the coziest room where you entertain and have people over, where you want to sit and chat. It’s the room you use the most and where I think there is the most design opportunity. I also always tell my friends that when they are thinking about decorating their homes, they don’t need an interior designer to do the entire home at once. They should start with the most important rooms, the living room, the bedroom and the kitchen. I think these three rooms are the ones where you spend the most time and need to feel most comfortable.

Fredericke: The most important room for me personally, because I am using it so passionately, is my kitchen. And I love open kitchen spaces that are connected to the living room. I often cook for people and I want to be with them while I am cooking. I just recently moved into a new house and of course the first thing I did was to design my own kitchen. I really like rooms which are not that easy to decorate with textiles. Whereas it’s clear that you need fabrics for the living room and the sleeping room, it can be a challenge in the entrance hall. This should be an interesting room, but it’s often the emptiest space. Designing it should almost be like an exhibition space. In real life, especially in a family home, it is always full with things. Guests enter your home and can explore your spirit. I love to show artwork and photographs that are important my creative family: work of my father who is a passionate laymen sculptor, the graffiti art of my son and souvenir photos from my partner, who is a music editor.

Elodie: I agree, my second favorite place would be the entrance. It’s the first thing you see when entering a home. And it’s like with a person: the first impression is really important. And for me, when I come back home I want to immediately feel at home. I have a small sofa with pillows in the entrance just to remove my jacket and shoes.

Allison: One of the images from my photoshoot shows the entrance way of the home that we shot. I hadn’t thought about decorating an entrance this grand before. But as I began scheming, the decision to make a screen with the elegant lampas and pillows for the bench in the linen floral created this elevated environment that set a welcoming tone for what was to come deeper into the house. So I agree that it’s really important.

Elodie: I just moved into a new very modernist home that we designed for three years with an architect and I wanted to install these beautiful fully embroidered curtains, like Sonja Delaunays. To feel like it was a museum on my wall, to give it a further function than only covering the windows.

Allison: You two live in these beautiful homes, I live in New York City where apartments tend to be much smaller. My living environment is a collection of treasures I’ve bought during my travels and it’s really layered together to feel super cozy. But for the longest time I wanted it to be more neutral because we work so much with color and... E: Aaah, I agree!

Fredericke: Me too. I had this problem with my clothes too, for the longest time I was only wearing black. Just shortly colors came back into my closet. A: For a very long time my apartment was more neutral, cozy but neutral. And only recently did I have this breakthrough, where I really wanted to add color. And I bought a new rug and I changed the chair and pillows. It’s very different now when I walk in and it just proves that making a subtle change like new throw pillows on your sofa can start to change the DNA of your environment. F: What made you change?

Allison: Honestly, I don’t know. I think maybe it has to do with the change of job positions. Being a design director means I can really be more focused at work. I can spend a lot more time on the layout and coloring of designs; being more methodical and having the time to give each design the respect that it deserves to make it perfect. Whereas before as a senior designer at another company I felt that I needed to get as much done as I possibly could in the shortest amount of time and I wasn’t really able to be intentional about it. I think my brain was a little more frantic. And now, because I can be a lot more focused during my day I have more opportunity to be more relaxed in my home.

Elodie: Decorating was a crucial part of my education because my family deals antiques. And since I was a child everything in my home changed frequently. My father would buy a painting and a day later it was sold. Sometimes a table would stay for five or six years, but eventually it got sold too. As a young kid I would change my bedroom making use of my father’s furniture storage. Still today I love the creative process and the fact that I can always open an new chapter. As soon as I move something in my home I personally have the feeling that also something new can happen. The page is now white and I can start again.

Fredericke: That’s funny because I had a very similar experience in my childhood. We were living in an little estate house built in the 1920’s in South West Germany right next to the French border. The style is quite similar to the house I live in now, with beautiful wooden floors, a fire place in the living room and a large garden that was given to miners back then for self-sufficiency. My mother, she would change the interior every year. Not only the interior but also the function of the rooms, the kitchen became the study; the living room was the sleeping room all of a sudden. I loved it. Of course she would start those projects right before big events like Christmas or a big birthday. I can remember our huge family parties, in rooms that slightly smelled of paint. I loved the creativity of my mother.

Allison: My experience is so different from both of yours. My parents still live in the house that they moved into when I was eight months. The house has changed, they’ve added an addition and it’s been redone, but the function of each room has always remained the same. It’s been frequently redecorated, my mother loves interiors and I think my love for interiors and textiles comes from her. If she had known that this was an opportunity for a profession, she would have gone into the arts. So the house itself is very much the house I grew up in. There is this familiarity to it and I think I really like that it has always very much felt like home.

Elodie: I changed homes 18 times with my parents due to the fact that they always loved to renovate and to change. We moved from the North of France to the South and back. F: Isn’t it interesting? Because it’s said that the Americans love to move and leave everything behind and start something new and the Europeans prefer to stay at one place.

Allison: Oh, I didn’t know that about us. (laughs) Even in NYC, and I’ve lived here for almost 15 years, I’m only in my third apartment. I lived in my first apartment with my best friend for a couple of years and then I moved off on my own to a studio, and now I live in a one bedroom apartment in the same building and on the same floor of my former studio apartment. It’s the apartment next door! And I never really thought about this but I think I find it really important to put down roots. Things change so much around me all the time that I like to think of home as a constant.

Fredericke: Nevertheless we often tell each other that something we say or do is so French, so American, and so German!

Allison: Everybody in Germany always reminds me how American I am. And I don’t fully know what that means or if it’s a compliment or not. I think there’s one thing about Americans: We’re loud! We make sure that you know that we’re here. Yesterday we had two international sales meetings in the morning and then at four o’clock the Americans arrived and the noise level was raised so high, and there was so much energy. I felt much more at home and I didn’t realize how much more relaxed I got when it was filled with noise. Maybe that’s very American.

Elodie: I would say the French lifestyle is very eclectic. And this you can also feel in the French people. You can be classical today and casual tomorrow. And this is a part of the way we design and how we live. I could live in a five star hotel and next time I prefer the one star hotel because the view is beautiful. It’s more about emotions and the inside of things. The French creative people I meet always work with their heart. And after my presentation people told me that I am talking with my heart. Maybe this is French? Secondly I like to be ‘comme l’air,’ relaxed and to not mind too much about things. But in the end I usually reach my goals.

Fredericke: I learned how German I am when I lived in Paris in 1999: always on time, always trying to anticipate and deeply in love with structures. And whereas you both can fall back to your culture when designing your collections it’s different for me. I can remember last year at Deco Off in January, when I represented Hodsoll McKenzie for the first time, before my first collection was set to launch in the fall. I met a highly important sales agent from the States and he was very critical from the start. He looked down on me and said: ‘A German wants to design a British collection for the American Market? Well, good luck!’ and I love quoting this, because this was my first question. Will I be able to achieve a credible result? However, I quickly realized that the brand identity, the special attention to natural materials, the soft colors and the deep roots in design history, is so me! Plus I had worked for British companies before and through my studies in design history I have a very clear idea of British lifestyle. I just had to find my own approach. So I created this British collection for the American market and all of a sudden in Russia people love the collection. This is a great opportunity for Hodsoll McKenzie. One design in particular is selling very strong in Italy and so this country is on my plate too. In the end we are creating collections for the global market.

Allison: Even though different countries have generalizations that we think are indicative of them, there is always going to be an exception, always something that surprises us about what’s popular. Even here at Deco Off I am seeing all the different countries response to the Travers collection. Even though it’s to be sold globally, America is at its core and I have to primarily design for the American market. This includes how we show the fabrics in the shoots. I was going through the books with one of our European agents and she was pointing to one of the photos and how we were showing the fabric and told me how American it was and that they would never use the fabric this way. Shortly after this she was showing the collection to a customer and they were interested in that same fabric, but maybe not to be used in the same way.

Elodie: Same here, Zimmer & Rohde asked me to design a French collection, but our main market is not France, it’s the US followed by Germany and then the UK. I like this challenge. It reminds me of the Haute Couture in France that nowadays sells mainly outside of France. I asked myself, what do people outside France think of as French style? So I adapt my answer to each part of the world when I design my collection. For instance, ‘Le Bouquet’ is more classical and would be Etamine for the UK while ‘Polynésie’ which is much more modern, would be Etamine for Belgium. What’s nice is that I chatted with our agent in Belgium and she told me the three assumed bestsellers for Belgium, and her choices are exactly what I designed with Belgium in mind.

Allison: There are a lot of similarities between the Hodsoll British design sensibility and Travers American design sensibility, what should set us apart is color. British colors are much more faded and dusty.

Fredericke: True, and there is also a difference in how we use documents. Your documents are normally very clear. For Hodsoll they look more vintage, very faded and even a bit disrupted. In my collection for 2019 I play a lot with this fading effect. For example, the print ‘Andresweald’ is a very abstract leaf print that reminds me of the marks of wet leaves on the concrete during autumn. I included a beautiful indigo blue, one of my personal favorite colors. The blues along with the aquas are typical Hodsoll colors. These light green and blue hues are very British. At the moment I see a lot of monochromatic interiors in greens and blues, even dark tones. Also every shade of greige, creating a beautiful warm and cold interplay, leaving their role of being the boring commercial classic and becoming really cool. I’m seeing plenty of monochrome rooms fully kept in greige and only one color spot, like a yellow chair.

Allison: Blue of every cast, shade and value is the main color story for Travers. From very light sky blue to very dark rich indigo to true porcelain blue and white. Blue is always going to be number one in America. Whereas my personal favorite color of the collection is the emerald green. I love real rich jewel tones.

Elodie: I love the greens too, and also the yellows and natural tones. And I am really obsessed with the yellow that was launched in my collection. Germany was so afraid about my yellow because it was so true. They wanted it to be more pale or with grey. But my yellow was the one you can find in nature. I was happy to talk to an editor this morning who loved particularly my yellow. So this was maybe really French, because I did not fight for my yellow but I challenged my direction to keep many yellows in the collection, and customers and editors appreciate it. Maybe it won’t sell as good as the other colors...

Allison: ... but it will for sure create the buzz! Just like the ‘Greensward Bouquet’ in the Travers collection which goes against our typical floral designs, which usually have a quirky stem and unusual flowers, like the Jacobean Floral. But the large scale and distressed detailing of this historical floral is so classical that it will always be popular.

Elodie: In case of Etamine it’s the multicolored flowers which are not traditional nor historical, and are a bit playful. That’s what I like about the Henri Matisse paintings and that’s what I like about Etamine. How about Hodsoll? F: We also will always work with historic documents, could be flowers but also geometric patterns. Great Britain is very proud of its arts and crafts movement in the 19th century. That’s why a lot of designs today date back to this time or refer to it. When we are talking about English florals, we often have the refined illustrations of William Morris, Owen Jones or Charles Rennie MacIntosh in mind. And that’s what also America relates with British design, even though there are plenty of important styles that came before and after, both of which are what I would like to explore for Hodsoll McKenzie.

Allison: I think it helps that we have each other in this way, that we are all three very different, from different countries with different approaches to how we do things, but are also completely supportive of one another. We are a nice trio, a team that cares for each other.

Fredericke: And though we are different, I feel that we share a vision and this makes us really strong together.

Kommentar - Textile Library

Mein Kommentar für die Ausgabe 11/19 des md Magazins.

Eine Bibliothek für Objektstoffe? Die wird es erstmals auf der Heimtextil 2020 geben. Ein Tool für Architekten, Innenarchitekten und Designer, das schon lange überfällig ist.

(…) Auf der einen Seite sind die Einsatzmöglichkeiten von Textilien nicht ohne weiteres vergleichbar mit denen anderer Werkstoffe, die man in der Innenarchitektur verarbeitet. Und obwohl sich das Angebot an Stein, Holz und Metall in letzter Zeit rasant erweitert, kann es noch lange nicht mit der Fülle an Materialkompositionen, Texturen, Dekoren, Farben und Funktionen mithalten, die im Stoff abgebildet werden können. Auf der anderen Seite legen Textilien auch bezüglich ihrer technischen Eigenschaften zu und ‧haben heute viele ihrer tradierten Schwächen überwunden, etwa Schmutzanfälligkeit oder Feuer‧gefährlichkeit. Damit wächst nicht nur das Angebot an Vorhangstoffen und Bezügen für den Objektbereich, sondern es wachsen auch deren Einsatzmöglichkeiten. Textilien empfehlen sich vielerorts als die bessere Alternative. So unterstützen Vorhänge in Krankenhäusern die Luftreinigung oder großflächige ‧Gewebe dienen als Dachbespannung.

Diese Vielfalt ist Fluch und Segen zugleich. Den Architekten, Innenarchitekten und Designern eröffnet sich ein reiches Gestaltungsspielfeld, gleichzeitig kommt ihnen jedoch das textile Angebot wie ein undurchdringlicher Dschungel vor. Immer mehr Stoffe drängen auf den Markt. Kollektionen wachsen und neue Anbieter, etwa aus dem erstarkenden asiatischen Raum, drängen nach Europa. Zudem sieht man der neuen Stoff‧generation ihre Funktionalität nicht mehr an. Outdoor sieht wie Indoor aus, Akustikstoffe sind transparent und Blackouts kommen wie natürliche Leinenqualitäten daher.

Textilverlage legen nach wie vor ihren kommerziellen Fokus auf den Einzelhandel, der sich vornehmlich für Dekor und Griff interessiert, so dass intelligente Funktionalitäten oft nur zaghaft kommuniziert werden. Das wirkt auf den anwendungsorientierten Architekten eher unglaubwürdig. Im Ergebnis bringen Verlage zwar technisch hoch spannende Textilien auf den Markt. Deren Features gehen aber gerne im umfangreichen dekorativen Angebot unter.

Dazu kommt: Designer sind im Kerngeschäft wenig mit Stoff befasst und verlieren sich auf der Suche nach dem Spezifischen gerne im Allgemeinen. Auch der ‧Architekt wird schnell der Muster überdrüssig und verharrt in seiner konservativen Haltung. Das heißt, er nutzt projektübergreifend die immer gleichen Stoffe oder er bevorzugt ‧Anbieter mit einem schmalen, auf sein Büro individuell zugeschnittenen ‧Produktportfolio. Im ungünstigsten Fall verzichtet er sogar ganz auf eine ‧innovative textile Lösung.

Dementsprechend bilden die zur Anwendung gekommenen Textilien nur sehr selten die Bandbreite ab, zu der ihre Hersteller heute technisch wie auch gestalterisch in der Lage sind. Das ist bedauerlich. Im Objektbau sowie jenen Privathäusern, die von professioneller Hand eingerichtet werden, liegt die Zukunft der Einrichtungstextilien. Der Einzelhandel verliert mehr und mehr an Umsatzkraft. (…)

Der gesamte Artikel ist hier zu lesen.

Editorial - Culinary Trims & Tassels

I was asked by Deco Home Magazine to reinterpret trims and tassels into typical German dishes.

Just a perfect opportunity to let off steam creatively.

Photos: Christian Hagemann

Co-Styling: Giulia Consiglio

Editorial - Deco Home X-Mas

Styling: FREDERICKE WINKLER & GIULIA CONSIGLIO

Fotos: RAPHAEL BRUGGEY | Patisserie: FRANZISKA OESER

Art Direction - Christmas Editorial

This is a production I realized with photo & styling duo Se7entyn9ne Berlin and which was partly published in Deco Home 04/19. It is always a pleasure working with those two gifted women.

Interview Werner Aisslinger

Welchen Herausforderungen wird sich die Branche in Zukunft Ihrer Meinung nach stellen müssen?

Werner Aisslinger: In Zukunft wird die allgemeine Bedrohung durch den Klimawandel für einen Paradigmenwechsel sorgen. Der Anspruch der Haltbarkeit einerseits wird mit dem Wunsch nach natürlichen Materialien kollidieren. Wir leben in einer Zeit, in der die Ökobilanz immer wichtiger wird und ich glaube in Zukunft wird der CO2-Fußabdruck eines Materials mehr im Fokus stehen und weniger die Lebensdauer, wie sie über synthetische Komponenten erzeugt wird.

Wie lassen sich solche Visionen mit den funktionalen Ansprüchen an Textilien vereinbaren?

Werner Aisslinger: Heute erscheint das noch unvereinbar, aber ich bin mir sicher, dass hier ein Umdenken stattfinden wird und dass Materialkriterien wie die Klimaneutralität und Kreislauffähigkeit, auch im Sinne des Reyclings, Upcyclings oder der Kompostierbarkeit, wichtiger werden als beispielsweise die Scheuerbeständigkeit. Man wird kürzere Zyklen in der Soft-Renovation zugunsten des besseren CO2-Fußabdrucks in Kauf nehmen.

Und man wird diese Anforderungen zukünftig auch durch neue Materialentwicklungen auf nachhaltigere Weise bedienen können. Zumindest hoffen wir das sehr, denn wir sind keine Entwickler von neuen Stoffen. Wir sind User und Customizer und sind auf die Innovationsfähigkeit der Textilbranche angewiesen.

Das gesamte Interview ist nachzulesen unter: https://www.md-mag.com/news/meinung/werner-aisslinger/

Styling - Home Story Kronberg

Outtake of the Home Story of Andreas Zimmer’s Property in Kronberg for DECO Home Magazine.

It was so much fun to do the Styling here.

Photos: Sabrina Rothe | Text: Anita Guepping

Art Direction - Bauhaus Still Life Editorial

Published in Deco Home 02/2019 (German version below)

And as soon as you think you have aesthetically absorbed the Bauhaus, you discover facets, personalities or documents that mix everything up again. This is the case with Walter Peterhans' photographic still lifes. The head of the photography department at the Bauhaus in Dessau since 1929 was known for his perfectionism, with which he arranged the objects of his motifs with tweezers with millimeter precision. And while this still sounds rather like Bauhaus, his motifs and those of his students tell a completely different story. They are wild, almost chaotic, playing with different materials and aggregate states. Some objects can only be seen in the reflection, others lie behind a glass filled with water and are optically distorted. Lace blankets meet trout, oranges meet mirrors, and the school building is recreated with the help of a cake. The goal was to experiment with seeing. And this is what we have made our task with the photo series.

Und sobald man glaubt, das Bauhaus für sich ästhetisch durchdrungen zu haben, entdeckt man Facetten, Persönlichkeiten oder Dokumente, die alles wieder durcheinander bringen. Mit den fotografischen Stillleben Walter Peterhans’ verhält es sich so. Der Leiter der Fotografieabteilung am Bauhaus in Dessau seit 1929 war bekannt für seinen Perfektionismus, mit dem er die Objekte seiner Motive mit der Pinzette millimetergenau anordnete. Und während sich dies noch ziemlich nach Bauhaus anhört, erzählen seine Motive und die seiner Schüler etwas ganz anderes. Sie sind wild, fast chaotisch, spielen mit unterschiedlichen Materialien und Aggregatszutänden. Manche Objekte sieht man nur in der Spiegelung, andere liegen hinter einem Glas gefüllt mit Wasser und werden optisch verzerrt. Es treffen Spitzendecken auf Forellen, Apfelsinen auf Spiegel und das Schulhaus wird mithilfe einer Torte nachgestellt. Ziel war das Experiment mit dem Sehen. Und dies haben wir uns mit der Fotostrecke zur Aufgabe gemacht.

Home Story - Frank Stüve

Erschienen in DECO Home 2/2019

Wenn der Showroom von Frank Stüve eines nicht ist, dann zurückhaltend. Mit sinnlichem Genuss wird das mondäne Italien flankiert von asiatischen Möbeln, während die Muster geradewegs aus einem südamerikanischen Urwald entsprungen zu sein scheinen. Doch obwohl die Räume so spontan wirken, merkt man sofort, dass Stüve nichts dem Zufall überlässt. Verschiedene Deckenleuchten, Steh- und Tischlampen erfüllen ein harmonisches Lichtkonzept, selbst die Reflektion der subtil glänzenden Teppiche wurde bedacht. Eine Komposition aus Beistelltischen, Poufs und Lehnstühlen schafft viele vertikale Ebenen. Der Stil ist männlich und weiblich zugleich: weiche und harte Oberflächen wechseln sich ab, ebenso wie glänzende und matte.

Stüves Königsdispziplin aber ist die Farbe und seine Räume sind eine Hommage an jede ihrer Nuancen. „Mein Vorbild ist die Natur, in der Farben scheinbar wild zusammentreffen und trotzdem eine feine Harmonie entsteht, einfach weil die Verhältnismäßigkeiten stimmen“, erklärt er. Und in der Tat sind die Räume trotz aller Buntheit nicht laut. „Wichtig ist, eine Farbe die Hauptrolle spielen zu lassen“, erklärt Stüve. Daher sei das Farbkonzept immer Ausgangspunkt: „Wir legen es schon im Grundriss an. Dadurch bekommt man gleich ein Gefühl für die Temperatur jedes Raums. Farben bringen Leben in einen Raum, durch sie entstehen wortwörtlich Lebensräume.“ (…)

Kommentar - Schlafwandel

Erschienen in md Magazin 11/18

“Ich habe sehr gut geschlafen.“ So lautet gewöhnlich die erste positive Rückmeldung eines Hotelgasts. ‧Eine knappe Zusammenfassung, in der viele Aspekte stecken, die eine gute Unterkunft ausmachen. Denn guter Schlaf versteht sich als die höchste Auszeichnung, als letzter ‧Beweis dafür, dass sich ein Gast rundum wohl und sicher fühlt. Schon Spätromantiker Friedrich Hebbel ‧bezeichnete den Schlaf als „ein ‧Hineinkriechen des Menschen in sich selbst“, die äußerste Form der Intimität.

Für die Hotellerie gehört der „Gute Schlaf“ traditionell zum Kerngeschäft. Neuerdings aber avanciert ihr Know-how rund um die Erholung zum Distinktionsmerkmal und wird als Ressource zur Kundenbindung entdeckt. Zwei Entwicklungen sind hierfür verantwortlich.

Interview - Jonathan Adler

Erschienen in Deco Home 04/2018

Die Geschichte von Jonathan Adler liest sich wie ein Werk von Paul Auster. Ein Kind aus New Jersey mit einer erstaunlichen Leidenschaft für die Töpferei bemüht sich um den Erfolg auf konventionellem Weg, bis er 27-jährig frustriert alles hinschmeißt und sich schwört, nie wieder einen normalen Job zu machen. Also bietet er seine Töpferware dem Luxuskaufhaus Barneys an, die prompt eine Bestellung aufgeben und Adler dazu zwingen, sich zu professionalisieren. Eine Kollaboration mit der Non-Profit-Organisation Aid to Artisans vernetzt den jungen Designer mit Kunsthandwerkern in Peru und schickt ihn endgültig auf den Weg hin zu seiner ganz eigenen Wohnwelt – von der Tasse bis zum Sofa – die wie keine andere Eleganz mit Humor verbindet. Denn Adler ist sich sicher: provokativ ist besser, Minimalismus ist Mist und Farben beißen sich nie. Und überhaupt solle ein Zuhause in erster Linie glücklich machen. Heute betreibt der Töpfer, Designer und Autor 30 Shops und richtet luxuriöse Privatwohnsitze, Restaurants und Hotels ein. Im Interview erklärt Jonathan Adler, wie er es schafft, als Nonkonformist so virtuos die Klaviatur der Etikette zu spielen.

Editorial Production - TW Russia

Mit der Sonderausgabe TW Russia richtet sich die TextilWirtschaft gezielt an den russischen Modemarkt. Im Rahmen der CPD in Düsseldorf und CPM in Moskau werden Kollektionen und Trends aus Deutschland in den Bereichen DOB, HAKA, Bodywear und Accessoires gezeigt und mit großer Bildsprache die Stärken deut- scher Labels für den russischen Markt beleuchtet. Die Sonderausgabe erscheint 2-sprachig (russisch/ deutsch) und richtet sich an russische Einkäufer und Projektentwickler.

Art Direction - Sommerbrise

Erschienen in Deco Home 03/2018

Photos & Set Design: Se7entyn9ne Berlin

Model: Klaudia Koj / McFit Models

Haare & Make-Up: Klara Stark

Feature - Interior in Iran

Auszug aus meinem Feature: Vorhang auf für den Iran - erschienen in Deco Home 03/2018

Während der Westen seinen Wesenskern im Weglassen sucht, ist die Spezialität des Ostens das Kombinieren. Farben, Formen und Stile finden mit einer gewissen Sorglosigkeit zueinander, die sich der westliche Designer in der Regel aus Angst zu Verkitschen nicht zugesteht. Von Innen betrachtet und auf die tatsächliche Wohnkultur im Land bezogen, erkennt man, dass der gestalterischen Opulenz durchaus eine Verknappung gegenübersteht, die ganz formale Gründe hat.

„Die wiederkehrenden Elemente des Iranischen Einrichtungsstils gehen zurück auf die Materialien, die zur Verfügung stehen. Erdtöne dominieren durch den Lehm, aus dem die Häuser vorzugsweise gebaut werden. Auch wird viel Stein und Holz, der vorherrschende Werkstoff für Möbel, verwendet. Farbe kommt durch die typisch iranischen Deko-Objekte, Teppiche und Fliesen, in den Raum. Wie auch in der Architektur spielt hier die Symmetrie eine wichtige Rolle. Die meisten Muster gehen auf sehr einfache, archetypische Formen zurück, etwa auf den Kreis oder das Quadrat, aber auch auf klassische florale Themen. Die Farben sind dabei eine Interpretation der Natur, man greift das Blau des Himmels oder das Gelb der Sonne auf. Insgesamt ist der iranische Stil sehr simpel und gleichzeitig sehr detailliert“, erklärt Lena Späth im Gespräch ihren Eindruck.

3. Platz - Bester Fachjournalist 2018

Für das Feature “Hautnah” für die TW home #2 über die Lederverarbeitung habe ich den Karl Theodor Vogel Preis erhalten.

Comment - Fairly isn't fair enough

excerpt of my comment: Fairly fair isn’t fair enough published in Sportswear International #284

Clearly, fair trade accords with my ideas of solidarity and human dignity and my basic value that all people, independent of their origins, their gender or their beliefs are equal. But this shouldn’t be the reason why I buy fair trade products. I would go as far as to say that sympathy is a fatal purchase driver. Because the global economy, of which all of us, including fair trade, are a part, will allow humanitarian parameters only in so far as they do not get in the way of the main goal, which is to make a profit. And any sympathy will only be extended as far as it doesn’t encroach on one’s own living standards. Thus the producer stays dependent on a consumer whose wealth is built on the shoulders of his poverty. Only when the manufacturer can afford the same products as the consumers at the other end of the world, can we talk of genuine fairness. But we won’t be able to achieve this state of affairs as long as they remain in the role of the invisible poor and thus legitimise the privileged customers to remain in their role.

The fast growing number of critical consumers is interested in the circumstances under which their goods are produced. Fair trade shortens the link between consumers and producers, provides transparency and promises an ecological chain of production. But the mere feasibility for the consumer to be able to buy fair trade products, marks them out as privileged. So the decision to buy fair trade is a choice of the lesser evil; from a position of privilege to attempt to introduce a little justice. Economic behaviour thus evolves into social behaviour. However, it remains a trade in indulgences. It is about breaking down this moralistic trickle-down effect, whereby the Western consumer passes on a piece of his wealth, in the form of consumption. The aim must be that they prefer fair trade goods, because they are – in every respect – the better offer.

J'N'C No 72 - Leitartikel "Size Matters"

Auszug aus meinem Leitartikel: Size Matters

Während man traditionell trotz aller Provokation den kleinsten gemeinsamen Nenner in standardisierten Körperproportionen, symmetrischen Gesichtern und jugendlicher Ebenmäßigkeit suchte, sind es heute vor allem die individuellen Körper, das Exotische und Kuriose, dass die Modewelt in Atem hält. Die Begeisterung ist groß und Aktivisten allerorts begrüßen zu Recht die neue Bühne für Antidiskriminierung. Dabei macht die Mode nichts anderes, als was sie schon immer gemacht hat, wenn sie von ihrer Kanzel auf die Straßen jenseits der Modemetropolen schaut, den Crazy Shit des realen Lebens aufsaugt und diesen stilisiert als Trend zurück auf die Straße bringt. Interessant dabei ist, dass durch den Hype des Kuriosen, das Kuriose selbst zur Normalität wird. Umso bizarrer, dass es sich beim Diversity-Trend um handfeste demographische Entwicklungen handelt, die noch dazu Massenphänomene sind. Man macht also die geheim gehaltene Normalität zum Kuriosum und treibt sie dann in den Mainstream. Was für ein schwindelerregender Gedanke.

Sportswear International #283 - Contribution

I contributed 20 pages about the most iconic fashion and design items from Italy to the Italian Issue of Sportswear International released in January 2018

Editorial "The Shift" - Production & Styling

for TextilWirtschaft home 2/17

Photos: Elizaveta Porodina

Model: Nella Roz

Hair & Make-Up: Stella von Senger

Licht: Josef Beyer

Assistenz: Caro Knitz

md Magazin 12/17 - Interview Ushi Tamborriello

Beitrag für das md Magazin (12/2017)

(...) „Vor Ihnen sitzt eine überzeugte Verfechterin des Inneren der Architektur,“ beginnt Ushi Tamborriello schmunzelnd das Gespräch und fasst, wie sich im Verlauf herausstellt, damit direkt die Besonderheit ihres Schaffens zusammen. Und das weit über den Umstand hinaus, dass sie Innenarchitektin ist und als solche ein breites Spektum an Innenräumen gestaltet, von Bäder- und Wellnessanlagen, Restaurants bis hin zu Ausstellungsarchitekturen. Der gestalterische rote Faden für die unterschiedlichen Wirkungsbereiche zeigt sich in der intensiven Beschäftigung mit dem Ort und seinen Funktionen im Zusammenspiel mit den menschlichen Bedürfnissen, die einem Projekt innewohnen.

„Im gemeinsamen Arbeiten am Projekt, stellt sich - in einer Zeit des völligen Umbruchs in nahezu allen Lebensbereichen – sehr früh die Frage nach einer verbindlichen Identität. Die vielen Entscheidungen, die im Verlauf zu fällen sind, fallen leichter und fundierter, wenn man ihnen mit einer Haltung begegnen kann. Neben der Reflektion, kommen dabei der sinnlichen Wahrnehmung und dem Erinnern tragende Rollen zu.“ Dies erreiche man mit dem Einsatz von Textilien besonders gut. „Im Zusammenhang mit der Differenzierung des Raumes ist gerade die textile Hülle eines der ältesten Kulturgüter, das wir kennen. Sie ist uns seit Jahrhunderten vertraut, bot uns Schutz vor klimatischen Einflüssen und vor unerwünschten Blicken. Und war schon in frühen Kulturen Trägerin erzählerischer Inhalte – man denke nur an die grossen Wandteppiche des Mittelalters, auf denen Geschehnisse der Menschheitsgeschichte in „Bildwirkereien“ festgehalten wurden.“

„Für mich ist Textil nicht einfach ein Material. Schon der Wortstamm ,texo’, das Weben, deutet auf die Verbindung von Qualitäten. Textile Materialien sind sowohl ästhetisch als auch funktional so vielfältig, dass sie kaum mit anderen Werkstoffen zu vergleichen sind“, erklärt die Designerin weiter. Und diese Vielfalt nehme mit der technologischen Entwicklung momentan rasant zu. Stoffe können heute schon leuchten, messen, senden, wärmen und sogar reinigend auf den Raum wirken.

Die Gründe, aus denen in den vergangenen Jahren in der Architektur oft auf textile Komponenten verzichtet wurde – etwa Nachteile in der Hygiene, Pflegeintensität oder eine fehlende Strapazierfähigkeit – seien folglich heute nicht mehr zutreffend.

„Über die viele Jahre vorherrschende Angst vor dem dekorativen Moment des Textilen im architektonischen Diskurs kann man heute nur lächeln“, stellt die Innenarchitektin fest. Neben dem technologischen Fortschritt seien es gerade die nahezu unbegrenzten Ausdrucksformen, die das Textil gestalterisch so wertvoll machen. So oder so müsse man den Gebrauch von Textilien neu lernen, so die Expertin. (...)

Photos: Jochen Splett

Editorial "Golden Age" - Production

for TextilWirtschaft home 2/2017

Photos & Styling: Se7entyn9ne Berlin

Editorial "Golden Age" – Production

for TextilWirtschaft home 2/2017

Photos & Styling: Se7entyn9ne Berlin

(EN) Interview Masaaki Kanai - Muji

For TextilWirtschaft home 2/2017/ Photos: Nic Oswald

(...)

How do you achieve the price while focusing so much on the product?

It is difficult to have a balance of quality, functionality and price. This is one reason why we survive, because it is difficult and we achieve it.

So what is the secret recipe then?

There is no secret recipe, but the difference between MUJI and other brands is our way of approaching product development. Normally, to add value to a product regular companies will add design and then keep on adding. At MUJI, we have a completely different method. We are trying to reduce or exclude unnecessary parts in order to simplify things. This difference in approach brings about a completely different product result. We are also constantly trying to improve our supply chain management.

Do you think by cutting out what is not necessary, the result is a sophisticated design which requires a certain kind of intellect to be understood?

Indeed. And this is a challenge for us as well. Maybe in Japan it is easier. The Bauhaus movement also tried to simplify things to make them functional. Traditionally in Japan, prior to the Bauhaus movement, we were seeking beauty in simplicity. It’s in our DNA to have this kind of attitude, and if people have grown up in this kind of environment they understand.

New and somehow challenging for the consumer, MUJI is also so affordable. Now we are in an era where price doesn’t determine luxury anymore. In another interview you said, that MUJI is the antithesis of today’s consumer habits. What do you mean?

There are two common natures in human beings. One is desire, and the second is that people are always concerned about what others think of them. Looking back to earlier societies there was no consumer society as there were no ratios. And everybody had the same hair colour and the same eye colour. People did not need to think about what other people thought of them because they were similar, apart from in terms of social milieu. Today in Vietnam for example new international brands, like H&M and Zara, are entering the market, and so what is happening is that new cultures are also entering the market. The people are quite shocked with a lot of information spread via magazines. People are using whitening skincare products to become fairer and using coloured contact lenses to have blue eyes. They’re dyeing their hair blond. They are trying to be fashionable and compare themselves to others. This is what has already happened in Japan in and under these circumstances people lost the idea of self. The power of trend is too strong. With this in mind, MUJI is the antithesis of consumer society in the way that we ask people to be themselves, to not lose their self-awareness, nor follow every trend. You have to find out the real value of things.

How does MUJI achieve this?

Under these circumstances there are still some people who are very conscious of what real values are. When the MUJI concept was born, it was developed by some important designers who targeted the people who know about those values. We don’t name the designer and we don’t name the brand on the products. It is just the product itself that counts.

This is also typical Bauhaus.

Yes, they have been very innovative. They strived to do away with ornamentation. That is why MUJI respects Bauhaus. They will celebrate 100 years shortly. Congratulations.

You say that you are not branding your product, but MUJI is a desirable brand.

Maybe we can’t say that anymore, that we are not a brand. You’re right. We often hear from different countries that MUJI is the new luxury because it is not branded. So the non-brand became a brand in itself, I guess.

(DE) Kommentar Tischkultur

Für TextilWirtschaft home 2/17 – Bild: Libeco Home

Eine Gesellschaft setzt sich bei heruntergelassenen Hosen auf Toiletten zu Tisch und unterhält sich über das Weltgeschehen, das mit am Tisch sitzende Kind wird zurechtgewiesen, als es Hunger bekundet – über solche Themen spreche man nicht – und ein Herr zieht sich diskret in eine Kabine zurück, in der er hinter verschlossener Tür ein Mittagessen einnimmt. In seinem Film „Das Gespenst der Freiheit“ von 1974 kehrt Luis Buñuel die Gepflogenheiten der Bougeoisie um und lässt groteske Szenen entstehen. Und hinterfragt, ob nicht allgemein anerkannte Konventionen gleichermaßen merkwürdig sein mögen. Wenn es oben reinkommt, ist es gesellig. Und wenn es unten rauskommt, sollte man lieber einen einsamen Ort aufsuchen?

Mit dem gedeckten Tisch hat sich der spanisch-mexikanische Filmemacher und Surrealist ein Motiv ausgesucht, an dem man in der Tat die gesamte Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit in ihrer Ambivalenz ablesen kann. Die Frage nach der Rolle der Tischwäsche damals und heute ist dabei vielleicht nicht ganz so umstritten. Allerdings war und ist auch sie dem sozialen Wandel unterworfen.

Schon in der ausgehenden Antike legte man Tücher auf kleine Tische, auf denen die Speisen gereicht wurden, während man im Liegen aß. Dazu standen Servietten und Fingerschalen mit Wasser zur Verfügung. Im Spätmittelalter saßen die Menschen auf Bänken und aßen von Tafeln, an denen Tücher angebracht waren, um sich Mund und Hände abzuwischen. Ab dem 13. Jahrhundert wurden die Tischplatten mit einem glatten Tuch bedeckt. Ein zweites legte man über die Kanten und ließ es bis zum Boden fallen. Die Gäste nutzten das umlaufende Tuch nach wie vor zum Reinigen von Händen und Mund und legten es über den Schoß, um ihre Kleidung zu schützen, quasi als überdimensionale, kollektive Serviette. Und die war dringend notwendig, denn Esswerkzeuge gab es seinerzeit nur spärlich, Messer steckten direkt im Mahl, man aß mit den Händen, später mit Löffeln, die man selbst - am Gürtel befestigt - mitbrachte. Erst ab dem 16. Jahrhundert setzte sich langsam die Gabel durch.

In der Renaissance sind immer noch Adel und Klerus die Epizentren der Zivilisation, von denen auch die Tischkultur ausgeht. Nicht umsonst dient das gemeinsame Mahl in den Weltreligionen als starkes Symbol: das Abendmahl Jesu’ als Zeichen seiner bleibenden Gegenwart oder „Sahūr“, die letzte Mahlzeit vor der islamischen Fastenzeit. Am Tisch finden das Religiöse und das Profane zueinander in Form von Gebeten, Ritualen und geselligem Beisammensein.

Die Tischdecke wird dank der virtuosen Damastweber jener Zeit zum textilen Zeugnis, indem sie das Stillleben-Motiv des gedeckten Tischs in den Stoff wirkten oder aufdruckten. Aus jener Zeit bleiben uns Blumenrapporte auf Tischdecken als Klassiker erhalten. Mit Aufkommen des Bürgertums im 18. Jahrhundert werden die Tischsitten Mittel zur sozialen Abgrenzung und verkomplizieren sich bis ins Unendliche. Eine wachsende Zahl an Besteck, nach komplexen Legesystemen angeordnet, setzt eine immer explizitere Reihenfolge von Abläufen voraus: Schneiden, zum Mund führen, nicht reden, Besteck exakt ablegen, Mund abtupfen, Serviette zurück auf den Schoß, schluckweise trinken, Nahrungsaufnahme wieder aufnehmen und so weiter und so fort. Diesen Regeln folgen wir in der westlichen Welt mehr oder minder bis heute und sie brachten selbst noch 1990 in dem Film „Pretty Woman“ die Prostituierte Vivian zum Verzweifeln, die als Begleitung des Brokers Edward Louis ein Geschäftsessen überstehen muss. Es gelingt ihr nicht, die Salatgabel auszumachen, und zu allem Überfluss springt ihr eine „Escargot“, eine Schnecke, aus der Zange geradewegs in die Hände eines Kellners. Das Versagen bei Tisch weist Vivian als unterprivilegiert aus, als „nicht dieser sozialen Schicht angehörig“. Dabei ist es nicht nur ihre fehlende Bildung, die zum Tragen kommt, sondern auch die fehlende Selbstkontrolle. Denn im Gegenteil zu anderen Distinktionsmitteln der Oberschicht, die womöglich vor allem Weltläufigkeit und Reichtum darstellen sollen, spielt beim guten Benehmen am Tisch die Disziplin eine tragende Rolle. Man wartet, beobachtet und übt sich im Zurückhalten unerwünschter Flatulenz.

Tischmanieren als Trennlinie zwischen der Noblesse der Oberschicht und der Barbarei des Proletariats. Und zwischen Lust und Anstand. Mit dem Ziel, den sinnlichen Akt des Essens in einen disziplinarischen Rahmen zu setzen. Dahinter steckt auch der protestantische Wunsch, den Geist über den Körper siegen zu lassen. Schließlich sind die historischen, religiösen und künstlerischen Analogien zwischen Essen und Erotik seit langem bekannt, sei es der Apfel der Erkenntnis, der Spargel als Phallus-Symbol oder Isoldes Zaubertrank. Lüsterne Frauen sind im Englischen „man-eater“ und lassen sich zu Deutsch „vernaschen“. Und einige Filmszenen, die als besonders erotisch in die Annalen der Kinogeschichte eingehen, handeln vom zügellosen Essen. In dem bis heute legendären Film „Das große Fressen“ von Marco Ferrreri aus dem Jahr 1973 wird durchgehend und gleichzeitig gegessen und kopuliert, während die Serviette nonchalant als Lätzchen im Hemd steckt. In „9 ½ Wochen“ aus dem Jahr 1986 von Adrian Lyne wird nicht nur auf Tischwäsche sondern gleich auf den ganzen Tisch verzichtet. Vor dem geöffneten Kühlschrank füttert John (Mickey Rourke) die junge Elizabeth (Kim Basinger) mit kaum zubereiteten Lebensmitteln direkt aus der Verpackung. Es wird verschüttet und ausgespuckt. Sie trinkt Milch direkt aus dem Krug, und die Hälfte läuft ihr am Mund vorbei. Es ist eine große Schweinerei, in jeglichem Sinn, denn die Völlerei endet im Geschlechtsakt. Dennoch: Kim Basinger trägt in der Szene einen blütenweißen Bademantel, der in diesem erotischen Bankett die Tischdecke ersetzt und ohne Reue beschmutzt wird. Das Textil ist also, wie in so vielen Lebenslagen, die Trennlinie zwischen Lust und Anstand. Die Tischdecke erfordert Disziplin beim Essen, um sie eben nicht zu verschmutzen. Die Serviette schützt vor dem Beflecken des Schoßes, vor diesem Hintergrund ein besonders delikates Bild.(...)

Sie möchten weiterlesen? Schreiben Sie mir...

(DE) Beitrag – md Magazin – Tue Gutes, rede darüber

Beitrag in der November-Ausgabe des md Magazins

Die Mode macht vor, dass Nachhaltigkeit heute nicht mehr nur ein Trend, sondern ein handfester Wettbewerbsvorteil ist. Wann zieht die Branche der Einrichtungstextilien nach? Oder ist sie etwa schon dabei und versäumt nur, darüber zu reden?

Handle stets so, dass kommende Generationen unter denselben oder besseren Bedingungen leben können wie wir heute. So lautet die einfachste und zugleich anspruchsvollste Defintion von Nachhaltigkeit. Wendet man sie auf die Industrie an, ergeben sich ökologische, soziale und gestalterische Richtlinien. Dabei wird der Begriff der Nachhaltigkeit gerne zuerst mit dem Ressourcenverbrauch in Verbindung gebracht. In Gedanken an kommende Generationen sollte man auf nachwachsende Rohstoffe setzen und davon nur so viel verbrauchen, wie in der Tat auch nachwachsen kann. Zudem sollten Wasser, Luft und Erde innerhalb der Produktionsprozesse geschont werden. Es leitet sich weiter eine unternehmerische Gesinnung in Form von Zuverlässigkeit, Transparenz und Verantwortungsbewusstsein gegenüber direkten oder indirekten Partnern ab. Wichtige Marker sind dabei die Preise, die Lieferbedingungen, die Risikoverteilung und die Planungssicherheit. Es gilt die Regel: Nicht die Machbarkeit sondern die Vertretbarkeit zählt, ungeachtet dessen, ob man mit dem Gestalter in Europa, dem Produzenten in Asien oder mit dem Kurier in der Region verhandelt. Zu Guterletzt ergeben sich Kriterien für das Produkt. Stets muss man sich fragen, ob Waren nicht effizienter hergestellt werden können, ob es auf Materialebene Neuerungen gibt und ob der Gebrauch noch dem Zeitgeist des Verbrauchers entspricht. Gleichzeitig ist man der Kulturgeschichte seiner Produkte verpflichtet. Denn es sind die Hersteller, die darüber entscheiden, ob althergebrachte Handwerkstechniken überleben – auch dies kann eine Form von Innovation sein. (...)

Kommentar – Incredible India

Für TextilWirtschaft home 2/17

In jeglicher Hinsicht ist Indien als aufstrebendes Entwicklungsland dem Wachstumswunder China auf den Fersen – schon seit Jahren. Was das Wachstum des Bruttoinlandsprodukts angeht, hat Indien mit 7,1% seinen Konkurrenten mit 6,7% schon im vergangenen Jahr überholt. Und fragt man Experten zu den Entwicklungs-Prognosen Indiens, heißt es immer wieder, der schlafende Riese sei gerade im Begriff aufzuwachen. Man solle nur an diese Millionen von Menschen denken, die sich derzeit aus der Armut in die neu entstehende Mittelschicht emporarbeiten.

Indien ist im Aufbruch, aber lange nicht so schnell, wie China es vorgemacht hat. Das sei auch ein unfairer Vergleich, heißt es dann postwendend. Immerhin habe Indien seine Entwicklung erst gut 15 Jahre später, 1991, begonnen und müsse als „größte Demokratie der Welt“ längere Entscheidungswege hinnehmen als sie im absolutistischen China üblich seien. Ohne hochwertige Rohstoffvorkommen und eine im Vergleich zur Größe der Volkswirtschaft bedeutende verarbeitende Industrie sind das Kapital Indiens seine gut 1,24 Milliarden Einwohner, im Durchschnitt 28 Jahre alt. Und jährlich kommen um die zwölf Millionen hinzu.

Anhand der Zahlen erkennt man die Diskrepanz zwischen den Potenzialen, die ohne Zweifel in dieser Volkswirtschaft schlummern, und der aktuellen Situation im Land. In den wachsenden Städten entsteht eine konsumfreudige Mittelschicht, die sowohl einheimischen als auch internationalen Unternehmen neue Profite verspricht. Die überwiegende Mehrheit der indischen Bevölkerung aber lebt in ländlichen Gebieten und ist dadurch wirtschaftlich benachteiligt. Mit 29 Bundesstaaten, 23 Amtssprachen und fünf Hauptreligionen ist das Land ohnehin sehr inhomogen. Die Hälfte der Bevölkerung arbeitet als Kleinbauern, die Landwirtschaft macht aber nicht einmal 20% der Gesamtwirtschaft aus. Neun von zehn Arbeitern sind im informellen Sektor beschäftigt und weder gegen Krankheit oder Arbeitsunfälle abgesichert noch haben sie Anspruch auf soziale Leistungen oder Altersversorgung. Sie zahlen auch keine Steuern. Gerade mal 5% aller dem Arbeitsmarkt zur Verfügung stehenden Menschen haben nach Regierungsangaben eine berufliche Qualifikation.

Andererseits leben in diesem Land die meisten Millionäre und Milliardäre weltweit. Spätestens seit einer Studie des Internationalen Währungsfonds aus dem Jahr 2015 aber wissen wir, dass der wachsende Reichtum der Topverdiener das Wirtschaftswachstum verlangsamt, während sich höhere Löhne unter den Geringverdienern positiv auf die gesamte Gesellschaft auswirken.

Die Armutsbekämpfung sowie die Bildungs- und Infrastruktur-Entwicklung sind große Aufgaben, die die hindu-nationalistische Regierung Indiens bewerkstelligen muss, um den Potenzialen des Landes gerecht zu werden. Vor allem beschäftigungsintensive Branchen stehen dabei im Fokus, um schnell viele Arbeitsplätze zu schaffen. Die Textilindustrie wird als Hoffnungsträger betrachtet. So steht Indien in der globalen Produktion von Baumwolle, Seide und Jute weltweit an zweiter Stelle. Auch in Bezug auf die Anzahl der Spinnereibetriebe ist das Land auf Platz zwei. Jeweils nach – wie sollte es anders sein – China. Immerhin: Bei der Zahl der Webereien haben sie den großen Konkurrenten schon überholt. (...)

Sie möchten weiterlesen? Schreiben Sie mir

(EN) contribution - Nothing new at the Eastern Front

My contribution to the German Issue of Sportswear International

It is somehow inconceivable, that we are still talking about the difference between West Germany. Come on! The reunification of the Federal Republic will soon be celebrating its 30th anniversary. The biggest current consumers of jeans, sportswear and casualwear cannot even actively remember that their home country was once divided; it is more or less just a chapter in their history textbooks. At best, it’s a story their parents tell at the dinner table, in which some talk about how hard they had it back in the day, while others reminisce about the good old days when they had everything they needed. Admittedly, although Germany was only divided for 41 years, less than two generations, in 1990 the state had to bring together two very contrary realities – on the one side, a prosperous, advanced West, and on the other, an economically run-down and culturally disrupted East, a scenario that even the best science fiction author could not have imagined. Twenty-eight years and more than two trillion euros of rebuilding investment later, the former GDR has obviously caught up with its supposed bigger brother in terms of infrastructure and appearance. More than that: made anew it even surpasses good old Germany with its new technologies and brightly lit streets. But sprucing up the former East doesn’t necessarily make it a successful market. It’s the culture, consisting of tradition and entrenched structures, that has to grow and its absence creates an invisible but perceptible border, which is especially apparent when looking at the minutiae of society – at retail businesses for consumer goods, for instance. (...)

(EN) Interview Petri Juslin - Marimekko

For TextilWirtschaft home 2/17

Mr Petri, what exactly is your role in the company?

My role has changed recently, about two months ago. I am now more focused on the long-term development of our print design ideas and deal less with the operational procedures and their deadlines. I supervise our new designers and their designs. Together with them we want to tackle long-term stylistic developments and also create a few new challenges for us. I am also responsible for our archives, which I am just reorganising to give us greater insight of what is still of value. For example, I’m looking for patterns that we haven’t used in a while but that are still really good from a modern-day perspective. Meanwhile, our young designers are bringing in new influences. I bring these two spheres together and make sure that the result bears a recognisable, yet fresh Marimekko DNA.

So you work closely with lots of designers. What’s that like?

Oh, yes, in my 30-year career at the company I’ve met and worked with many designers and searched for solutions on how to print their ideas on fabric. I get the impression that a lot of people believe that design means you are given a picture by a designer and then you just print it out on fabric. But that’s not how good designs come about. The design process begins with the designer having an idea, which we then discuss as a team to think about what we can do with it. Often, the designer has to develop many variations of their idea, until they come up with something that works well as a print, as well as being functional, and satisfying the formal requirements of our customers and lives up to their aesthetic standards.

How do you achieve that?